Adaptive learning algorithms are changing how students learn. They adjust content in real time based on how fast someone answers questions, where they struggle, and even how long they pause before clicking. But behind the scenes, these systems aren’t neutral. They make decisions-sometimes silently-that can reinforce bias, mislead learners, or even lock students into learning paths that don’t serve them. Without clear ethical guardrails, these tools risk doing more harm than good.

What Adaptive Learning Algorithms Actually Do

At their core, adaptive learning algorithms analyze student behavior to predict what they need next. If a student keeps missing questions about fractions, the system might loop them back to basic arithmetic. If another student breezes through algebra, it skips ahead to calculus. That sounds helpful, right? But the algorithm doesn’t know why the student struggled. Did they miss class? Are they stressed? Do they learn better visually than textually? Most systems don’t ask. They just react to data points.

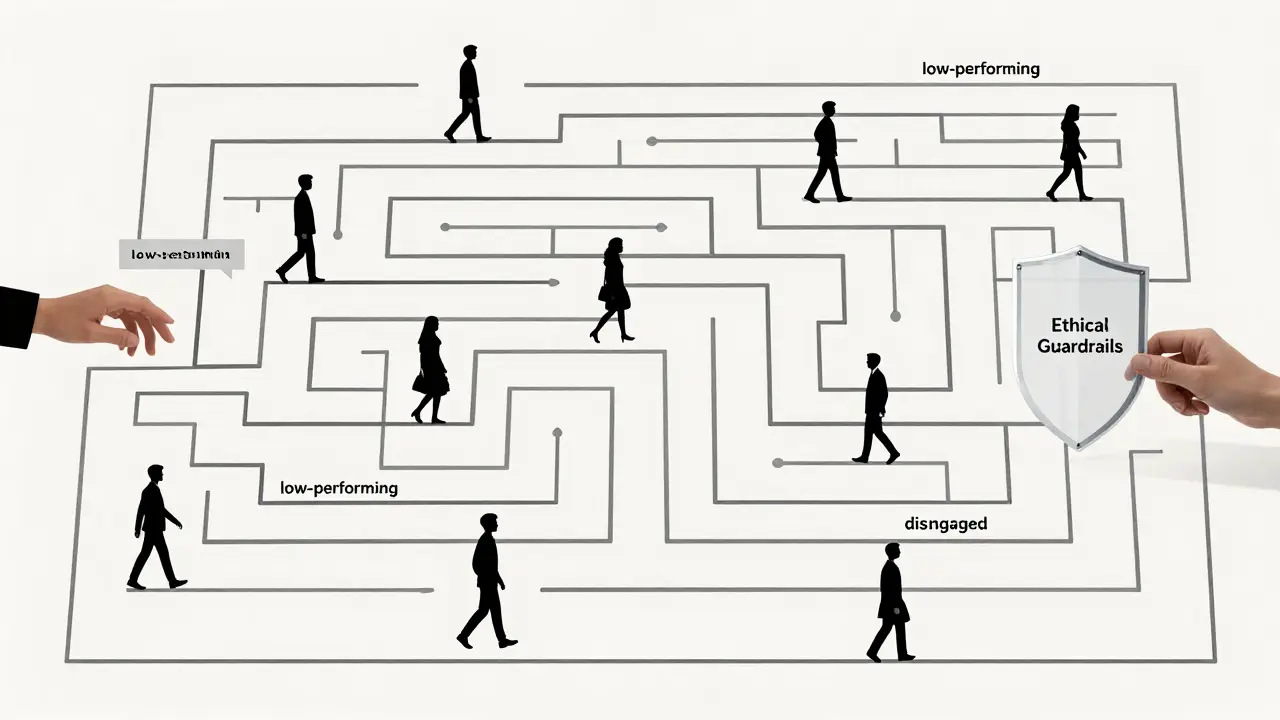

These systems rely on patterns from millions of past interactions. That means they learn from what worked for most people-not what’s right for each individual. A student from a rural school with limited internet access might get flagged as "low-performing" not because they’re behind, but because they can’t access video lessons. The algorithm doesn’t see the barrier; it sees the drop in engagement and adjusts accordingly.

The Hidden Biases in Personalized Learning

One of the biggest risks is algorithmic bias. If the training data mostly comes from students in urban, high-income districts, the algorithm will assume that’s the norm. Studies from Stanford’s Graduate School of Education found that adaptive platforms in U.S. public schools were 30% more likely to recommend advanced material to white and Asian students than to Black and Latino students with identical test scores. Why? Because the system learned that students from certain demographics historically moved faster through the curriculum-and assumed that pattern would repeat.

Language is another blind spot. If a student speaks English as a second language, the algorithm might misinterpret their slower response time as lack of understanding, not language processing delay. It could then lower the difficulty level, not realizing the student could handle the content if it were presented differently. That’s not personalization-it’s limitation.

Even something as simple as time-of-day usage matters. Students who work part-time jobs or care for siblings often study late at night. If the algorithm only tracks engagement during school hours, it might assume they’re disengaged. That can trigger interventions-like automated emails to parents-that don’t reflect reality.

Why Transparency Matters More Than Efficiency

Most adaptive systems are black boxes. Teachers don’t know how the algorithm makes decisions. Students have no idea why they’re being pushed toward certain topics. Parents can’t challenge a recommendation because they don’t understand the logic behind it.

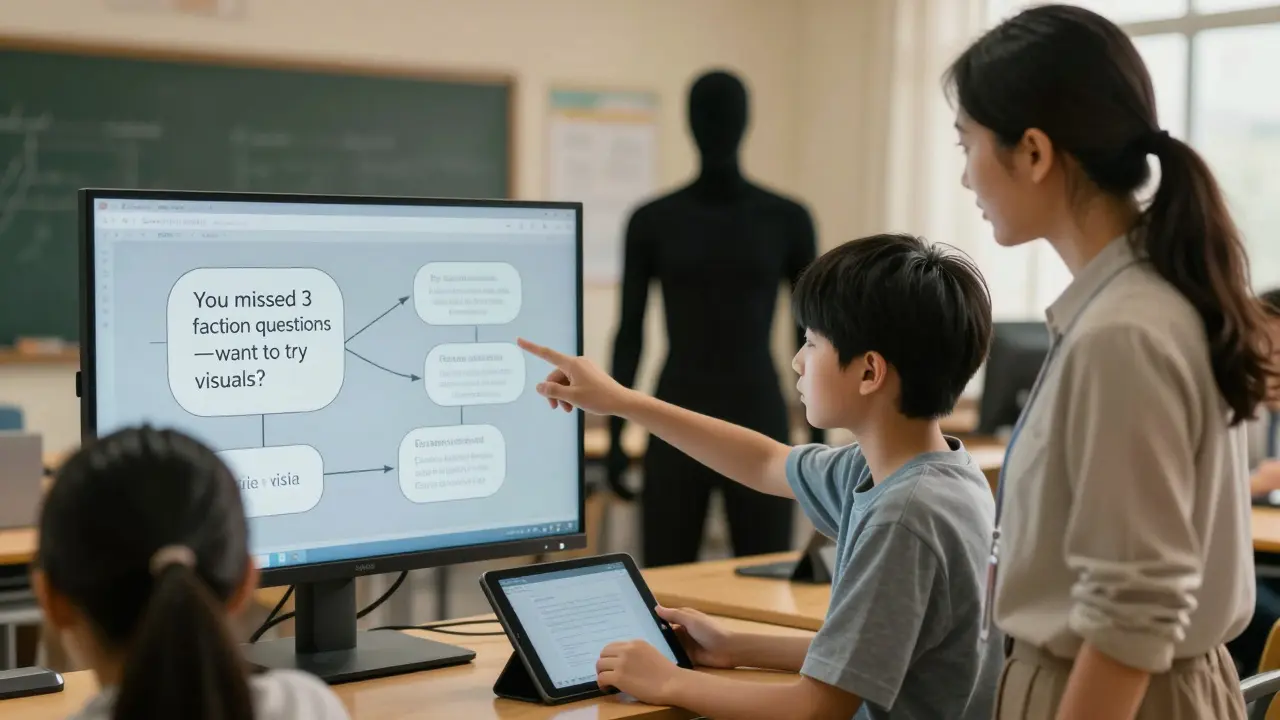

Transparency isn’t just nice to have-it’s a requirement. If a student is repeatedly routed into remedial modules, they should be able to ask: "Why?" and get a clear answer. The system should explain: "You’ve missed three questions on quadratic equations in the last week. Would you like to try a visual explanation?" Not: "You’re struggling. Let’s go back."

Some platforms, like Knewton and DreamBox, now offer dashboards that show teachers the reasoning behind recommendations. But that’s still the exception. Most systems prioritize speed over clarity. That’s dangerous. When educators can’t audit decisions, they can’t correct them.

Who Gets Left Behind When Algorithms Decide

Adaptive learning was supposed to close achievement gaps. Instead, it’s widening them-for certain groups.

Students with learning disabilities often get misclassified. A student with dyslexia might read slowly, but understand content deeply. An algorithm might assume they’re not ready for complex texts, locking them into simplified versions that don’t challenge them. Over time, they lose confidence and stop trying.

Neurodivergent learners, like those with ADHD or autism, may interact with content differently. They might skip around, revisit topics randomly, or take long breaks. Many systems interpret that as disengagement and reduce challenge. That’s the opposite of what these students need. They need flexibility, not reduction.

And what about students who don’t fit neatly into categories? Non-binary learners, multilingual households, cultural learners who value collaborative problem-solving over individual testing-these students often get flattened into data points that don’t reflect their reality.

Building Ethical Guardrails: Practical Steps

Here’s what real ethical guardrails look like in practice:

- Require human oversight-No algorithm should make permanent placement decisions without teacher review. If a student is flagged for remediation, a teacher should get a notification and a chance to override it.

- Use diverse training data-Platforms must include data from rural, low-income, multilingual, and neurodivergent learners. If a system only learns from 20% of the student population, it’s not adaptive-it’s exclusionary.

- Let students control their path-Offer an "I want to try this" option. If the algorithm recommends a review module, the student should be able to say, "I’d rather try the harder version." Autonomy matters.

- Explain decisions simply-Use plain language: "You’ve answered 5 out of 8 questions correctly. Would you like to try a different format?" Not: "Your proficiency score is 62%. Proceeding to Tier 2."

- Audit for bias quarterly-Publish results. If a system shows a 25% disparity in recommendation rates across racial groups, it’s not working. It needs fixing, not just tweaking.

Some schools in New Zealand and Finland have started requiring algorithmic impact assessments before adopting any adaptive tool. They ask: Who might this hurt? How do we know it’s fair? What happens if it’s wrong? These aren’t bureaucratic hurdles-they’re ethical necessities.

Teachers Are the Missing Link

Adaptive systems are tools, not replacements. The best outcomes happen when teachers use them as assistants, not authorities.

A teacher who sees a student flagged as "at risk" by the algorithm can check in: "I noticed you’ve been stuck on this section. What’s making it hard?" That human connection is what the algorithm can’t replicate. The algorithm can say, "You need more practice." The teacher can say, "Let’s try this with blocks instead of numbers."

Professional development for teachers must include AI literacy. They need to know how these systems work, what their limits are, and how to question them. No teacher should be expected to trust a black box.

What’s at Stake

Every time an algorithm makes a decision about a student’s learning path, it’s shaping their future. A child labeled as "not ready" for advanced math might never take it. A student who’s pushed too fast might burn out. A learner who’s ignored because their behavior doesn’t match the model might give up.

These aren’t hypothetical risks. They’re happening now. In 2024, the U.S. Department of Education issued a warning to schools using unvetted adaptive platforms, citing cases where students were misdirected into lower-level tracks based on flawed data.

Technology isn’t the problem. It’s the lack of accountability. We don’t let machines grade essays without oversight. We don’t let them prescribe medication without a doctor. Why do we let them shape education?

Adaptive learning can be powerful. But only if we build it with ethics at its core-not as an afterthought, but as the foundation.

Can adaptive learning algorithms be biased even if they don’t use race or gender data?

Yes. Algorithms don’t need to see race or gender to be biased. They use proxies-like zip code, device type, time spent on tasks, or even font size preferences-that correlate with demographic groups. A student using an older smartphone might be flagged as "low-engagement" because their device loads videos slowly. That’s not about ability-it’s about access. These hidden correlations can reinforce systemic inequalities without anyone realizing it.

Who is responsible when an algorithm makes a harmful decision?

Responsibility is shared. The vendor who built the algorithm must design it ethically and provide transparency tools. The school that purchases it must vet it for bias and train staff. The teacher must question its recommendations. And the student and family deserve a voice in how it’s used. No single party should bear full blame-or full control.

Are there any regulations for ethical adaptive learning systems?

Not many yet, but changes are coming. The European Union’s AI Act classifies education AI as "high-risk," requiring transparency and human review. In the U.S., states like California and New York are drafting laws requiring algorithmic impact reports for ed-tech tools. Some school districts now require vendors to share their training data and testing results before purchase. These are early steps, but they’re necessary.

How can parents check if their child’s learning platform is ethical?

Ask three questions: Can I see how the system makes decisions? Does it explain why my child is being recommended certain content? Has the school tested this tool for bias across different student groups? If the answer to any is no, push for more information. Ethical platforms will welcome these questions-they’re not hiding anything.

Do adaptive systems improve learning outcomes?

Sometimes-but only when designed well. A 2023 meta-analysis of 47 studies found that adaptive tools improved test scores by an average of 8% in math and 5% in reading. But when the systems had poor data, no human oversight, or biased training sets, outcomes were worse than traditional methods. The difference isn’t the technology-it’s how it’s used.

Next Steps for Schools and Developers

For schools: Don’t buy adaptive tools just because they’re trendy. Demand transparency reports, bias audits, and teacher training. Start small-pilot one tool with one grade level. Track who benefits and who gets left out.

For developers: Build with ethics from day one. Include diverse user testing. Let educators and students help design the interface. Don’t assume efficiency equals effectiveness. The goal isn’t to make the system smarter-it’s to make learning fairer.

Adaptive learning has potential. But potential without principles is just another form of control. The real innovation isn’t in the algorithm-it’s in the courage to ask: "Who is this for? And who might it hurt?"

Comments

Chris Heffron

Honestly? This is the kind of post that makes me want to cry... and also update my syllabus. 😅

Adrienne Temple

I’ve seen this happen in my classroom. A kid with dyslexia gets stuck in basic modules because the algorithm thinks slow = dumb. But she reads Shakespeare for fun at home. The system doesn’t see that. We need to fix this, not just talk about it.

Sandy Dog

OKAY BUT HAVE YOU SEEN WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THE ALGORITHM THINKS A KID IS 'DISENGAGED' BECAUSE THEY'RE ON THEIR PHONE DURING HOMEWORK?? 🤯 Like, my niece is a night owl who studies while her little brother naps. The system sends her mom a notification saying 'Your child is falling behind.' Mom panics. Kid cries. Teacher is confused. This isn't personalized learning-it's digital gaslighting. 😭

Nick Rios

I appreciate how you laid this out. It’s not about rejecting tech-it’s about demanding better from it. Teachers need to be part of the design process, not just the last person to clean up the mess.

Amanda Harkins

we keep calling it 'adaptive' like it's some magical brain. but it's just a fancy spreadsheet with a glow-up. and if the data's garbage? the output's garbage. and kids pay the price.

Jeanie Watson

I’m not surprised. Same thing happened with automated grading in my district. Thought it’d save time. Ended up giving a kid a D because they used 'their' instead of 'they’re'. The system didn’t know it was a non-native speaker. We had to manually override it for 17 students.

Tom Mikota

So let me get this straight… we’re letting a piece of software that doesn’t know what a comma is decide whether a 14-year-old gets to take algebra? And we call this progress? 😂

Mark Tipton

Let’s be real-this isn’t about bias. It’s about control. The companies behind these platforms are selling outcomes, not education. They’re using student data to train predictive models for corporate hiring pipelines. The moment a kid is flagged as 'low-potential,' they’re already being sorted into a labor tier. This isn’t an algorithmic flaw-it’s a feature. And the Department of Education knows it. They just don’t want to admit it.

Adithya M

In India, we see this too. Kids in villages get stuck with text-only modules because video streaming is slow. The system assumes they’re not trying. But their phone data runs out by noon. No one asks why. Just push the button harder. This needs global standards, not just US reforms.

Jessica McGirt

I’ve started asking my students: 'If you could change one thing about how this app works, what would it be?' The answers are eye-opening. One said, 'It never asks if I’m tired.' Another: 'It thinks I don’t care because I don’t click fast.' We need to let them talk back to the machine.

Donald Sullivan

I work in ed-tech. I’ve seen the code. The 'fairness' features are checkboxes. They’re not real. The model still prioritizes speed, completion, and engagement metrics that favor privileged kids. The vendors don’t care if it’s fair-they care if it looks good in the pitch deck.

Tina van Schelt

Imagine if your therapist made decisions based on how fast you typed your responses. 'You took 37 seconds to say you're sad. That’s low emotional intelligence. Let’s try a different approach.' That’s what we’re doing to kids. We’re reducing humanity to latency.

Aaron Elliott

The premise of this piece is fundamentally flawed. Ethical guardrails are a distraction from the core issue: education is not a data optimization problem. To treat it as such is to commit a category error of monumental proportions. The algorithm does not 'learn'-it correlates. The student does not 'struggle'-they experience epistemic friction. To reduce pedagogy to predictive analytics is to surrender the moral authority of teaching to the logic of the marketplace. One cannot engineer equity through regression models. One must cultivate it through dialogue, presence, and radical attentiveness. The real 'black box' is not the algorithm-it is the neoliberal ideology that equates efficiency with excellence, and quantification with truth.